Chantelle Bongubukhosi Ncube

In many African societies, the ability to speak fluent English is treated as a marker of prestige, often overshadowing the significance of mother tongues. In cities like Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, this reality is visible in schools, workplaces, and social circles, where English proficiency is prized and those who struggle with the language face mockery. This phenomenon is not unique to Zimbabwe but is echoed across the continent, creating a deep divide that threatens to erode the rich linguistic diversity of Africa.

The Rise of English as a Prestige Language

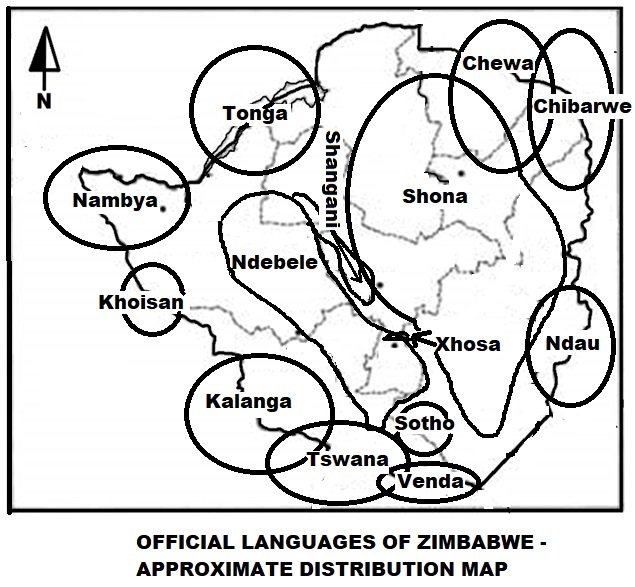

English, often perceived as the language of success, modernity, and upward mobility, has found a privileged place in many African nations. Post-colonial Africa, inheriting English from colonial rule, has allowed the language to dominate spheres such as education, business, and politics. In Zimbabwe, for example, English is the official language of instruction from primary school onwards, with indigenous languages like Ndebele and Shona often relegated to casual, informal spaces.

This prioritization of English can be seen in how students are groomed to master it as a sign of intelligence. In fact, research conducted by the African Language Association found that 78% of African students felt pressured to perform well in English-based exams as these determined future career prospects. In Bulawayo, where both Ndebele and English are widely spoken, young people often report facing ridicule from peers for speaking in Ndebele, or for speaking “broken” English, viewed as a sign of incompetence.

The Cultural Consequences

The rising preference for English has sparked concerns over the gradual extinction of African languages. UNESCO estimates that more than 200 African languages are currently endangered, with some predicted to disappear within the next 50 years. Each lost language represents the loss of cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and identity.

In Zimbabwe, young people often view speaking indigenous languages as a mark of inferiority, leading many parents to raise their children predominantly in English. This phenomenon, prevalent in urban areas like Bulawayo, detaches children from their roots. A 2022 study conducted at the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) revealed that 65% of children in urban Zimbabwe are more proficient in English than in their native tongue by age 10, raising alarms about the future of the Ndebele and Shona languages.

One Bulawayo-based linguist, Dr. Thabani Nyathi, states: “Language carries culture, wisdom, and community values. When we lose our languages, we lose the ability to transfer key aspects of our heritage to the next generation. The emphasis on English at the expense of our mother tongues is undermining our African identity.”

*Intelligence Beyond Language

The assumption that fluency in English equals intelligence is deeply flawed and problematic. Many Africans are multilingual, proficient in their native languages and at least one colonial language, demonstrating cognitive flexibility and adaptability. However, English is still wrongly upheld as the sole indicator of intellect.

A report from the African Academy of Languages (ACALAN) showed that 80% of African students who excel in their native languages but struggle in English are often labeled as “less intelligent,” leading to unfair academic assessments. In schools across Africa, children are tested primarily in English, which not only overlooks their cultural knowledge but also limits the expression of their intellectual capabilities. This system fails to accommodate linguistic diversity and the richness that native languages contribute to learning.

In an interview with a Bulawayo-based teacher, Ms. Moyo, she explained how this bias affects students: “We’ve had bright children who struggle with English and are unable to express their ideas fully, but when you communicate with them in Ndebele, you realize how brilliant they are. Our education system should embrace both English and our indigenous languages.”

To preserve African languages and cultural identity, linguistic diversity must be embraced as an asset rather than a liability. Initiatives such as mother-tongue-based education systems, as seen in Ethiopia, are a step in the right direction. Ethiopia’s education system allows primary school students to learn in their native languages, with English introduced as a secondary language. This model could be adopted in countries like Zimbabwe to ensure that children develop a strong foundation in their mother tongues before transitioning to English for secondary-level education.

Parents, educators, and policymakers must also work to shift the narrative around language and intelligence. Recognizing that fluency in English is not the sole measure of intelligence will open up opportunities for students who excel in indigenous languages and broaden their potential to contribute meaningfully to society.

In Zimbabwe, efforts like the National Language Policy, which promotes the use of all indigenous languages in public spaces, should be expanded to include active implementation in schools, government, and media. Educating the public about the importance of linguistic diversity is crucial to reversing the damage caused by English dominance.

As Africans, it is essential to question the prestige we attach to English fluency and how it influences our view of intelligence, identity, and culture. Mocking those who are not proficient in English alienates them from society and undermines the significance of African languages. While English plays a practical role in global communication, it should not be at the expense of our linguistic heritage. Embracing our mother tongues, alongside English, is a step toward preserving the cultural wealth of Africa for future generations.

Africa’s strength lies in its diversity, and this includes the diverse languages that have shaped its history. It is time to take pride in our languages and reject the narrative that fluency in a colonial language defines our worth or intellect.

Zim GBC News©2024